One of the joys and privilege of working with young children is to observe them as they play, talk, think and learn. Watching children gives us a real insight into their lives; their thinking; their emotions and their unique personalities. It is our window into their development and our invitation to play alongside, joining in as a play partner, a co-constructor and as a teacher[1]. Susan Isaacs recognised this in 1926 and wrote about the child’s world,

It cannot, of course, be very easy for us to gain a clear idea of what the world is like to a very young child, just because it must be so different from our own. But by patient listening to the talk of even little children, and watching what they do, with the one purpose of understanding them, we can imaginatively feel their fears and angers, their bewilderments and triumphs; we can wish their wishes, see their pictures and think their thoughts (Isaacs’s, 1929 p15).

Observation is a Statutory Duty (2.1, EYFS 2014) and accepted practice even though it is not a new process; think Susan Isaacs in 1926 and her well documented observations of children's play and development.

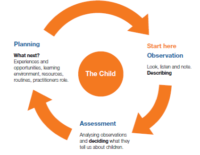

The Statutory Duty (2.1) of observation, assessment and planning is interpreted very well in Development Matters (p.4) and makes important links to good practice. It is very clear that the process begins with Observation and Describing what children are doing in their play and activities.

However there are certain things which worry me about the way we observe and how we put our observations to good use. For example we often use observations as a ‘shopping list’, looking for the things we want to see and tick off. How many colours does the child know? Can they count numbers up to 10? Do children know the names of a triangle, square and circle?

Focusing on check-lists and looking for surface level knowledge means that we miss the more complex, unique nature of children’s thinking, deeper level understanding and learning. We don’t look for or describe the mastery of their learning; the way children set their own problems and then look for solutions and the possibility questions they ask with their pointed fingers, questioning eyes and curious conversations.

If we make a single snap-shot observation, often jotted on a post-it-note as we pass by, and then make another one on our return what have we missed? It’s like an observation sandwich with the filling missing; we have failed to notice the most important part which involved the child or children working through a process of their own creation.

Good observation is about being able to do the following;

If we make sure that our observations primarily recognise HOW children are learning rather than WHAT they are learning we will have a much more secure foundation on which to base our Assessments. This means looking at the Characteristics of Effective Learning before you do anything else. You will this see much more in terms of children’s development and progress – you see them (from the start) as thinkers and learners. Try assessing (analysing and deciding what it is you have seen) by looking for the Characteristics of Effective Learning first. Then consider the WHAT….

WHAT children learn means looking at the knowledge, skills and content of learning; some of which can be found in Development Matters in the Areas of Learning and the Unique Child. A word of warning here though! Development Matters is not the complete guide to children’s development, if it was it would be enormous.

HOW and WHAT children learn is vast, especially in the first 5 years of their lives. To recognise and understand this we need to use a range of tools, not just Development Matters, so that we have a more robust understanding of children’s development. We can then make much more informed, professional judgements about their learning and the progress they make.

Good Assessment happens when we have observed well and then interpreted what we have seen in the most accurate way, taking many things into consideration, so that we can see the progress children are making, and how we can further support their thinking, learning and development. Avoiding a ‘tick-list’ approach to assessment is crucial for the reasons explained above and to avoid a narrow view of children’s potential development and progress. Development Matters affirms this in the footer of every page,

Children develop at their own rates, and in their own ways. The development statements and their order should not be taken as necessary steps for individual children. They should not be used as checklists. The age/stage bands overlap because these are not fixed age boundaries but suggest a typical range of development.

The key to this is triangulating the judgements you make in your assessments by considering other aspects of child development such as;

All these perspectives will lead to a better understanding of children’s development and help you to make stronger more robust, informed judgements about their development, learning and progress. Planning for children’s next steps and extending development will also be much more informed and personalised as you have a much clearer understanding of what experiences, opportunities, and resources to provide.

Look out for Part 2 - Mapping children's progress !

[1] We are all teachers – anyone who enters the lives of young children is a teacher as they play, talk, support and extend development and learning