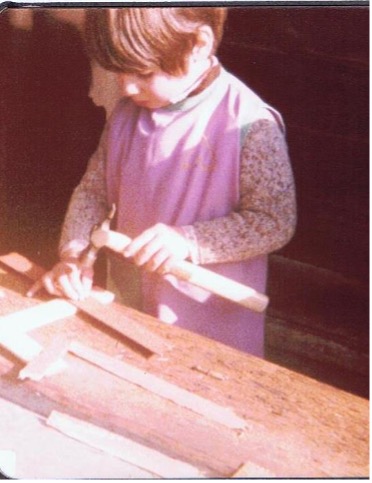

In 1978, as part of my NNEB training I wrote about Aiden who was at Nursery School, he would have been about 54 months old and was the focus of my observational child study. This is what I observed about him:

Aiden has developed an interest in woodwork and is very good at it; he can hammer nails in very well without any assistance. Aiden tries to do things before he will ask anyone to help him and he found that he didn’t really need any help doing woodwork.

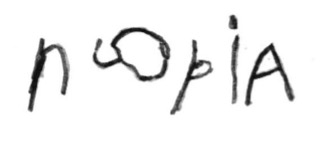

I was also fascinated by the way he wrote his name, “I asked him to write his name for me recently and he did it without any assistance which he couldn’t do before, but for some reason he wrote it backwards which is quite unusual. He is left handed and he started from the left-hand side of the paper and worked inwards.”

Aiden was showing me what a competent, capable and independent thinker and learner he was; following his ideas and interests as he persisted and deepened his skills in woodwork and writing. I was involved in what we would now call ‘Responsible Pedagogy’ (EYFSP, 2017, p. 11) observing Aiden in a context where he is able to “demonstrate his understanding, learning and development”. These are the observations we need to undertake as they are “the most reliable way of building up an accurate picture of children’s development and learning” (EYFSP, 2017, p. 11).

Reflecting back on these observations from 40 years ago I still get excited by observing children and seeing their development, thinking and learning unfolding in front of me. I didn’t realise at the time just how important it was to tune into children’s ideas and interests and question why and how they did certain things in their play and activities. I was learning to become an observer of children and an under-stander of child development as that was at the root of my role working with young children in schools and nurseries. I was using “observational assessment to understand children’s learning” (EYFSP, 2017, p.11).

In 2018 observation is still fundamental to those who work with young children (0-7yrs). Effective teachers/practitioners tune into children’s development, language and thinking through their observations and then use this to extend their understanding and learning. The EYFS Statutory Framework (2017, 2.1) states observation is an ‘integral part of learning and development’ (p. 13) and the Ofsted Early years inspection handbook, Good grade descriptor for teaching, learning and assessment, describes the process as adults…

Observe carefully, question skilfully and listen perceptively to children during activities in order to re-shape activities and give children explanations that improve their learning (2015, 150068, p. 39).

Despite becoming a Statutory Duty, the use of skilled observation as part of the assessment process in the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) has become politicised and misunderstood by many including teachers, head teachers and policy makers who seek to reduce a critical professional and pedagogical approach to quick, superficial binary tests which tell us little about young children’s deeper levels of thinking and learning (Whitebread, 2012; Siraj-Blatchford, 2002). Not only does this undervalue the potential of children’s development it lowers adults’ aspirations for children and depresses the progress and achievement children can potentially make.

The Tickell Review of the EYFS (2010) recognised the value of observation and its fundamental role in exemplary early years practice:

Observational assessment is integral to effective early years provision. The evidence clearly shows this type of assessment lies at the heart of providing a supporting and stimulating environment for every child (p. 30)

And made a recommendation that:

…guidance simply sets out that assessment should be based primarily on the observation of daily activities that illustrate children’s embedded learning (p.35)

At the same time Tickell (2010) made a strong recommendation for initial training and continuing professional development to ensure an ‘up to date knowledge of child development’ and a ‘defining standard and status for expert practitioners’ with an ‘emphasis on practical application, theoretical understanding and reflective practice’ (p. 46). Since then several other reviews (Nutbrown, 2012, Early Years Workforce Strategy 2017; SEED, 2017) have expressed similar research-based views.

The Study of Early Education and Development: Good Practice in Early Education (SEED, 2017) a study commissioned by the DfE, identified observational approaches as central to exemplary early years practice in all sectors (including schools) and as an indicator of high quality which has underpinned children’s progress. Other indicators include:

Observation, knowing when to observe and describing what we see (verbally and in documentation) and then interpreting what we have seen, is a professional skill which is fundamental to teaching and learning. Just as doctors need to diagnose their patients, teachers/practitioners need to look at the evidence and make decisions about how to support children’s development. Mary Jane Drummond articulates this in a respectful child-centred way in the following:

When we work with young children, when we play and talk with them, when we watch them and everything they do, we are witnessing a fascinating and inspiring process: we are seeing young children learn. As we think about what we see, and try to understand it, we have embarked on the process that I call ‘assessment’. I am using the term to describe the ways in which, in our everyday practice, we observe children’s learning, strive to understand it, and then put our understanding to good use. (Drummond, M.J., 1993, p. 13)

It was from Drummond’s description of the observation process that the exceptional assessment practices in New Zealand were developed, using narrative Learning Stories and looking deeply into children’s development and how they learn. I saw this first hand during a study visit to New Zealand early years centres in 2014 and wrote in my BLOG ‘What strikes me is the level of knowledge and understanding of the practitioners – they know their child development and can articulate what they see children doing very well’ (See ‘Happy Children’ at https://watchmegrow.uk/2014/02/happy-children/).

Grenier (2018) talks about ‘keen observation’ as practitioners get to know their children and ‘notice what is important about their development and learning’. He also makes a crucial point here about ensuring that there is a ‘rich learning environment and a rich curriculum’ to ensure that there is much for practitioners to notice about ‘what children know and can do, how they think and develop their ideas, and what sort of misconceptions and barriers to learning they may have’ (p. 14).

The National Strategies (2004-2011) saw observation at the heart of professional practice and documented this in many of their publications including Progress Matters – Reviewing and enhancing young children’s development (2009) where they stated that:

Observation is an integral part of professional interactions with children and is identified in the EYFS as a key to effective practice. Early years practitioners need to know their children well and record, where appropriate, their observations in quick notes or lively narratives (p. 6)

Alison Peacock (Chief Executive of the Chartered College of Teaching) at a recent conference (January 2018) spoke about ‘Professional learning without Limits’ and the importance of teachers and practitioners having ‘pedagogical conversations’ about their children.

Peacock called this ‘research-based pedagogy’ where teachers/practitioners make opportunities to ’really deeply’ look at what is ‘going on’ in their settings including ‘observation of children and talking about their thinking’. The observation process or cycle actually follows a research based approach through gathering the qualitative evidence of children’s engagement in their play and activities, interpreting or analysing the evidence and then drawing conclusions about what might happen as a result. This is research that is grounded in practice with the whole experience of observation actually deepening teacher/practitioner knowledge and skills in a cycle of continual professional development. Observing children is one of the best ways to fine tune your knowledge of child development and how they think and learn.

Observation is not without its challenges, which have been many, including a reductionist view of children’s development through simplistic and superficial proposals for baseline assessment at the start of the Reception year. These types of assessment, which do not involve observing children in the context they are most familiar with and acknowledging them as experts in their own field of play, are often quick fixes for Government accountability and are increasingly taking over professionally informed insights of what young children are actually capable of thinking about and learning.

Ofsted have also contributed to the undermining of professional observation practices in their recent ‘Bold Beginnings’ Report (2017) by contradicting the Standards and Testing Agency’s Early Years Foundation Stage Profile handbook (2017) which states, “Practitioners need to observe learning which children have initiated rather than only focusing on what children do when prompted” (p. 17). Ofsted has suggested that:

The majority of teachers did not agree that observational assessment was the most reliable form of assessment as stated in the EYFSP handbook. They felt that statements such as the one above lessened the importance of assessment as part of teaching (Ofsted, 2017, p. 26)

This statement also contradicts the EYFS Statutory Framework (2.1) and findings from major reviews and research quoted at the beginning of this paper.

Interestingly the Bold Beginnings report also states, “Many teachers commented that assessment, undertaken as they were teaching, allowed them to adjust their activity in the moment” (Ofsted 2017, p. 26), however, in order to do this ‘adjusting in the moment’ teachers/practitioners will be intuitively ‘observing in the moment’ and making informed decisions about how to support and extend children’s development and learning. It’s called good teaching and is responding to child-led thinking and learning which frequently leads to episodes of sustained shared thinking (Siraj – Blatchford, 2002). This is sophisticated observation at a skilled professional level – it is hard to teach effectively without it. It develops with experience, practice and a good knowledge of child development which forms part of teachers and practitioner’s observation tool kits.

The Observation Tool Kit is a virtual representation of the knowledge, skills and experience needed to make accurate, objective and insightful observations of children. It is a metaphor for all the inherent professional skills that are used when we observe children, strive to understand what we seen and put that understanding to good use.

As the Tool Kit develops the more skilful teachers and practitioners will become at making informed professional judgements about children’s development and progress. It is a crucial part of early years professional practice and should begin in initial training on the complex development of young children and How they learn. It develops further through observing children and documenting what you see; supported by reflective practice, opportunities to share and discuss what has been seen and keeping an open-mind; it strengthens (triangulates) the judgements you make about children’s progress.

The Tool Kit includes:

A good knowledge of child development - the more you know and understand about children’s development the more informed your evaluation and decisions about progress and next steps

The characteristics of effective learning – understanding HOW children learn helps you to see WHAT they are learning and HOW they are thinking. They include many dispositions and skills which underpin life-long learning. Recognising these as you observe children reveals their attitudes to learning, including personal, social and emotional development

Development of Speech, language and communication – having a good understanding of language development and its relationship to cognitive and social/emotional development

Levels of Involvement and Well-Being – the Leuven Involvement and Well-being Scales give practitioners/teachers crucial insights into children’s development, learning and progress

Sustained Shared Thinking – is mainly observed in child-initiated/led play between children and with adults. As we observe SST we can see many aspects of children’s deeper levels of thinking, communication and talking. It is made up of many aspects of children’s development including cognitive self-regulation.

Children’s Schema; threads of thinking – understanding children’s schematic development from birth will support the interpretation of children’s play, thinking and development; including the links between schematic development and early concept formation

Child-led Play: knowing children’s interests and fascinations – child-led play, activities and interests are the window into children’s thinking, development and learning. The more we observe and understand the clearer our insight into the child’s world, development and progress

SEND – developing an understanding of SEND and early intervention. Supporting the child and family through being informed, aware and documenting progress – taking small steps

Working together with parents and other partners - Having a broader insight of the child’s world, their family, culture, home and community will help you to see the child’s development in context.

Using the Observation Tool Kit means that practitioners/teachers draw on and think about many other aspects of children’s development, not just Development Matters, which only gives the thinnest slice of children’s developmental potential. As Nancy Stewart (2016) points out, “The statements in Development Matters are common examples of how children might develop and give a general picture of progression, but they are by no means the whole story”. She goes on to say, “We need to be thinking for ourselves as we decide what is important in a situation, and in deciding what comes next. It requires both judgement and creativity, and is not as simple as following a set of instructions”.

Building a professional Tool Kit takes time but the more practitioners/teachers know about children’s development and learning the stronger their practice will become. In developing these observation and assessment skills they will be more informed, confident and accurate in articulating the holistic developmental progress of young children. Above all we need to make assessment for learning work for children and bring the joy back into observing them as they play, talk, think and learn.

Callanan, M. et al (Jan 2017) Study of Early Education and Development: Good Practice in Early Education (SEED), Research Report, DfE

Chilvers, D. (2014) Happy Children, accessed via the WatchMeGrow Blog at https://watchmegrow.uk/2014/02/happy-children/

DCFS (2009) Progress Matters – Reviewing and enhancing young children’s development, https://www.foundationyears.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/progress-matters.pdf

Department for Education (March 2017) Early Years Workforce Strategy

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-years-workforce-strategy

Drummond, M. J. (1993) Assessing Children’s Learning, David Fulton

Grenier, J, Finch, S, and Vollans, C. (2018) Celebrating Children’s Learning, David Fulton

Ofsted (August 2015, 150068), Early Years Inspection Handbook

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-years-inspection-handbook-from-september-2015

Nutbrown, C. (June 2012) FOUNDATIONS FOR QUALITY The independent review of early education and childcare qualifications Final Report (Nutbrown Review), DFE

Siraj-Blatchford, I. et al (2002) Researching Effective Pedagogy in the Early Years (REPEY), DFES and the Institute of Education. Research Report 356

Standards and Testing Agency (2016) EYFSP Handbook 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/564249/2017_EYFSP_handbook_v1.1.pdf

Stewart, N. (May 2016) Development Matters: A landscape of possibilities, not a roadmap, https://eyfs.info/articles.html/teaching-and-learning/development-matters-a-landscape-of-possibilities-not-a-roadmap-r205/

Whitebread, D. (2012) Developmental Psychology on Early Childhood Education, Sage

[1] The Observation and Assessment Tool Kit© self-assessment is being developed by Di Chilvers as part of the Development Map. More information can be found at https://watchmegrow.uk/2016/07/decide-progress-child-made/